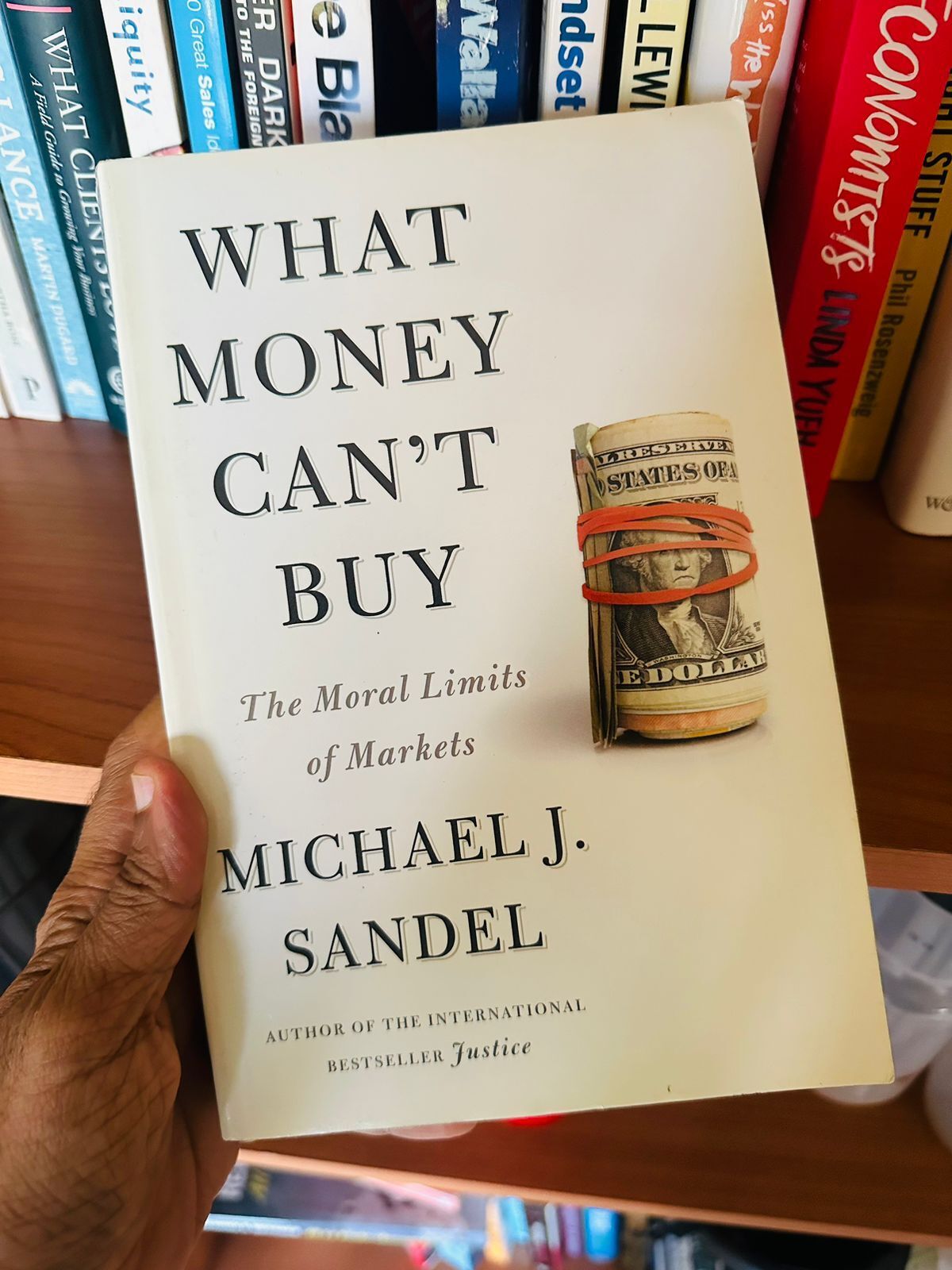

HomeWhat Money Can’t Buy By Michael SandelBook SummaryWhat Money Can’t Buy By Michael Sandel

June 22, 2024

What Money Can’t Buy By Michael Sandel

My top 25 points:

- We live at a time when everything can be bought and sold. Over the past three decades, markets — and market values — have come to govern our lives as never before. We didn’t arrive at this condition through any deliberate choice. It is almost as if it came upon us.

- Today, the logic of buying and selling no longer applies to material goods alone but increasingly governs the whole of life.

- The era began in the 80s when Reagan and Thatcher proclaimed their conviction that markets, not government, held the key to prosperity and freedom. The end of the Cold War encouraged a sense of market triumphalism, an assumption that our system was the best. And it continued in the 90s, with the market-friendly liberalism of Clinton and Blair.

- Today, that faith is in doubt. The era of market triumphalism has come to an end. The financial crisis did more than cast doubt on the ability of markets to allocate risk efficiently. It also prompted a widespread sense that markets have become detached from morals and that we need somehow to reconnect them.

- Market triumphalism is not correlated with any particular level of economic wealth or economic development. The US and Europe had achieved a very high level of economic development before this market triumphalist idea set in.

- While it’s certainly true that greed played a role in the financial crisis, something bigger is at stake. The most fateful change the unfolded during the past three decades was not an increase in greed. It was the expansion of markets, and of market values, into spheres of life where they don’t belong.

- To contend with this condition, we need to do more than inveigh against greed; we need to rethink the role that markets should play in our society. We need a public debate about what it means to keep markets in their place. To have this debate, we need to think through the moral limits of markets. We need to ask whether there are some things money should not buy.

- So many examples of the encroachment of markets:

- The proliferation of for-profit schools, hospitals, and prisons, and the outsourcing of war to private military contractors.

- The eclipse of public police forces by private security firms.

- Big Pharma’s aggressive marketing of drugs to consumers in rich countries.

- The reach of commercial advertising into public schools.

- The outsourcing of pregnancy to surrogate mothers in the developing world.

- The buying and selling, by companies and countries, of the right to pollute.

- A system of campaign finance that permits the buying and selling of elections.

- Why worry that we’re moving toward a society in which everything is up for sale? For two reasons: one is about inequality; the other is about corruption. Consider inequality. In a society where everything is for sale, life is harder for those of modest means. The more money can buy, the more affluence (or lack of it) matters.

- If the only advantage of affluence were the ability to buy yachts, sports cars, and fancy vacations, inequalities of income wouldn’t matter very much. But as money comes to buy more and more — political influence, good medical care, a home in a safe neighborhood rather than a crime-ridden one, access to elite schools rather than failing ones — the distribution of income and wealth looms larger and larger.

- That explains why the last few decades have been especially hard on poor and middle-class families. Not only has the gap between rich and poor widened, the commodification of everything has sharpened the sting of inequality by making money matter more.

- The second reason we should hesitate to put everything up for sale is about the corrosive tendency of markets. That’s because markets don’t only allocate goods; they also express and promote certain attitudes toward the goods being exchanged. Paying kids to read books might get them to read more, but also teach them to regard reading as a chore rather than a source of intrinsic satisfaction. Auctioning seats in the freshman class to the highest bidders might raise revenue but also erode the integrity of the college and the value of its diploma.

- Economists often assume that markets are inert, that they do not affect the goods they exchange. But this is untrue. Markets leave their mark. Sometimes, market values crowd out nonmarket values worth caring about.

- If you look at the economic textbook of Paul Samuelson, which was the most influential economic textbook in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s, he defined economics by its subject matter—inflation, unemployment, foreign trade, the money supply etc. Today if you look at most economics textbooks, economics is presented as a science of social choice that applies not only to material goods but to every decision we make, whether it’s to get married, or to stay married, whether to have children and how to educate those children, or how to look after our health. Economics rests on un-argued assumptions that need to be examined.

- If you go back to Adam Smith, you find the idea that markets and market forces operate as an invisible hand. But today, when economics is increasingly defined as the science of incentive, the use of incentives involves active intervention, either by an economist or a policy maker, in using financial inducements to motivate behavior. Recently we’ve heard a lot of talk of incentivizing. What it reflects is the trend toward using financial inducements to motivate a wide range of human activity, like paying school children to do well on standardized tests.

- Of course, people disagree about what values are worth caring about, and why. So, to decide what money should — and should not — be able to buy, we have to decide what values should govern the various domains of social and civic life.

- We don’t allow children to be bought and sold on the market because children are not regarded as consumer goods but as beings worthy of love and care. We don’t allow citizens to sell their votes because we believe that civic duties are not private property but public responsibilities. To outsource them is to demean them, to value them in the wrong way.

- When people are engaged in an activity they consider intrinsically worthwhile, offering them money may weaken their motivation by depreciating or ‘crowding out’ their intrinsic interest or commitment.

- Imprinting things with corporate logos changes their meaning. Markets leave their mark. Product placement spoils the integrity of books and corrupts the relationship of author and reader. Tattooed body ads objectify and demean the people paid to wear them. Commercials in classrooms undermine the educational purpose of schools.

- We may have to let markets do their work in certain areas even though we recognize that we are paying a certain moral cost. For example, permits to hunt endangered black rhinos were issued by the South African government starting in 2004. This sounds barbaric. But the reality is rather different. The animals were being poached to extinction. The Govt sells a limited number of hunting permits, at a prohibitively expensive cost, and then ploughs the money into protecting the rest. It has worked. Poaching has diminished and rhino numbers have bounced back. Commodifying, it appears, can work.

- At a time of rising inequality, the marketization of everything means that people of affluence and people of modest means lead increasingly separate lives. We live and work and shop and play in different places. Our children go to different schools. It’s not good for democracy, nor is it a satisfying way to live.

- Democracy does not require perfect equality, but it does require that citizens share in a common life. What matters is that people of different backgrounds and social positions encounter one another, and bump up against one another, in the course of everyday life. For this is how we learn to negotiate and abide our differences, and how we come to care for the common good.

- We shy away from public debate that touch on questions on the good life and the meaning of goods and how to value various goods and social practices such as these. We need to overcome that reluctance, if we’re to improve the state of our public discourse

- One of the effects of the market triumphalism of the 30 years is that our politics has been emptied out of substantive moral discourse, and as a result democratic politics is increasingly unsatisfying. Democratic politics is increasingly about narrow managerial, technocratic concerns rather than with larger questions of ethics and justice and the meaning of the common good.

- And so, in the end, the question of markets is really a question about how we want to live together. Do we want a society where everything is up for sale? Or are there certain moral and civic goods that markets do not honor and money cannot buy?